CfD AR7a in focus: project finance considerations

QMPF considers how recent changes to the CfD framework within wider shifting market policy might impact project finance solutions for onshore wind and solar developments.

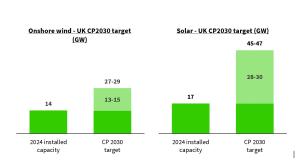

The UK’s Contracts for Difference (“CfD”) Allocation Round 7 is the latest competitive auction to support new renewable energy projects. The auction is split between an AR7 round for offshore wind technologies and an AR7a round for all other technologies. The AR7a round will be key to reaching the UK’s Clean Power 2030 targets; installed onshore wind capacity needs to be doubled, and solar tripled, in the next 5 years vs. end of 2024 levels to meet these targets.

With the bid process being widely commented upon, QMPF has explored how the new contract terms and features of AR7a may influence lenders’ appetite for lending to projects once the CfD auction is complete and the winners, and losers, are announced. We have included a brief explainer to project finance as an appendix for those unfamiliar with the terminology and structure.

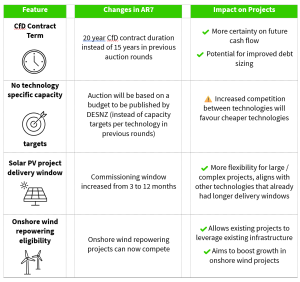

Contracts for Difference, key terms and new features for AR7a

Broadly, AR7a offers more flexibility and longer term certainty for bidders but also introduces more competition between technologies. These changes aim to award CfDs to projects that offer best value for money and provide bidders with some additional certainty in their project. However, as we discuss below, there are material risks for projects which will remain.

Impact on project finance

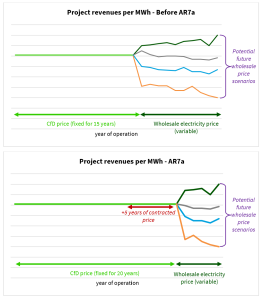

Those successful in the AR7a auction will own projects with a longer contract (20 years) than previous auction rounds (15 years). Developers may bid a lower CfD strike price in AR7a given the longer CfD term on offer. However, the extended contract length provides more certainty on the future revenue pricing between years 15 and 20.

Consequently, funders are likely to offer debt which considers repayment over a longer period. Previously, banks considered cash flows to the end of the CfD plus a small tail when assessing the project’s ability to repay (e.g. 17-18 years). That period will likely extend to 20 years, which, all else being equal, may allow projects to borrow more from lenders (subject to gearing limits). Higher gearing would ultimately reduce the developer’s equity investment requirement, should lower the overall weighted average cost of capital for projects and could increase equity return (or will have allowed developers to bid for a lower strike price to achieve the same IRR).

While lenders may consider a longer period of cash flows in assessing how much debt a project can support, they are still likely to be constrained to offering a loan tenor of c. 5-7 years. The project would be expected to refinance the loan once matures (in effect there would be a large amount of debt outstanding at the end of the initial 5-7 year tenor of the loan).

However, there are still unaddressed risks for projects

Developers are facing a number of risks and uncertainties which may materially impact project capital costs, ability to capture revenue and the variability of operating costs. Some of these will either crystalise or fall away as a project reaches final investment decision and financial close, others will change on an ongoing basis. All risks will need to be considered when assessing project viability and funding options. Some of the key risks and their impact on projects’ ability to support debt are included below.

TNUoS charge increase

Transmission Network Use of System (TNUoS) charges are expected to significantly increase for projects located further away from demand (such as those located in the North of Scotland) but may reduce for those located nearer demand (e.g. in the South of England), or become more of a benefit where demand outstrips supply. The National Energy System Operator’s latest forecast published in September suggested charges in Scotland, where TNUoS could account for over 40% of a project’s operating costs, could more than double by 2030. Recent consultations aimed at providing more certainty and / or parity on costs across geographies (cap and floor model or removing the locational factor) have both been rejected by Ofgem this year.

The AR7a CfD mechanism does not allow for adjustments to reflect changes in TNUoS, and as such it will remain a risk for developers post CfD award. Bidders should have considered potential TNUoS costs in their auction bid price, so there should be an allowance for the cost within any CfD price awarded. However, there remains a material risk due to the uncertainty around the extent of the future changes impacting a substantial operating cost (or benefit).

Lenders will be keen to understand a project’s exposure to TNUoS going forward and its ability to service debt in scenarios where TNUoS charges are higher, or payments received are lower, than those forecast in the model. This is an area where policy is likely to change over the coming months / years and will be monitored closely by developers and lenders alike.

Negative pricing

Under AR7a, and other recent CfD rounds, CfD top up payments are not paid when the reference day ahead electricity market price is negative. This is to avoid incentivising generators to produce electricity and export to the grid when there is a clear market price signal that there is insufficient demand. The occurrence of negative price periods has been increasing in recent years which reduces project revenue for CfD projects. The impact of negative pricing is potentially less material than TNUoS given the proportion of time throughout the year that there have been negative day ahead prices. This has been less than 2% over the last five years (although historic performance should not be relied on for forecasts).

Negative pricing is likely to continue in the near term. Over the long term, there is an argument that the occurrence of negative price periods should reduce. This could occur as support for older assets, which may have support tariffs which incentivise bids at negative prices, ends. Additionally, more recent and new generating assets should be incentivised to bid at zero or above so they do not lose their CfD top-up.

Lenders will be keen to see downside scenarios modelled which illustrate project cash flows where negative prices become more prevalent. They will also wish to understand project specific mitigations, such as including a contingency within forecasts assumptions, intraday PPA management and co-locating assets (e.g. storage).

Capital expenditure inflation and FX risk

Capital expenditure renewable energy assets has increased over the past few years at a higher rate than general inflation due to supply chain pressures and grid infrastructure upgrades. Developers also face exchange rate risk for a significant proportion of their capital expenditure. Turbines or solar panels are typically sourced from companies abroad who seek to pass through some, or all, exchange rate risk to developers. Market or commodity price inflation may also be passed through under some supply contracts.

Developers should have considered this within their CfD bid strategy. However, the risk remains that there is a mismatch between CfD inflation, at CPI, and the true cost changes on capital expenditure (inflation and FX movements) between CfD award and financial close, and thereafter if the exposure remains unhedged. This divergence was one of the contributing factors to a number of AR4 CfD contracts being cancelled as the projects were no longer financially viable.

Lenders will look for capital costs to be contracted on a fixed price basis and, where there is any remaining inflation or FX exposure, for this to be managed e.g. through contingencies and / or via hedging instruments.

Reformed National Pricing

Following an initial phase of the Review of Electricity Market Arrangements (REMA) assessment, the UK Government indicated in July 2025 that it intends to reform the energy system under a national rather than locational or zonal pricing basis. While this may protect the market price for generators located in remote areas, while limiting this price for generators in high consumption area, the exact reforms which will be implemented are unknown. Any impact on existing CfD arrangements will need to be monitored, although the market is hopeful, and is assuming, that existing CfD contracts, including AR7a, should be protected to help maintain investor confidence in delivering new renewable projects. This will also assist in meeting the Government’s Clean Power targets.

How can QMPF help?

QMPF’s energy team has extensive experience advising on project financing and related activity (CfD auction, hedging, M&A) across onshore wind, solar, storage, bioenergy and heat. Our team develops investment grade financial models to forecast project performance under various scenarios to support project finance transactions. We can provide early stage support to allow developers to consider appropriate financing strategies and conduct competitive funding processes on behalf of developers, managing the process through to financial close.

Appendix: What do we mean by project finance?

Project finance is debt which is provided to a project vehicle and its future cash flows. It is underpinned by a structured, long term approach that isolates the project’s assets, contracts and cash flows from its sponsors. It is non-recourse to those sponsors; if the project fails, an investor can only lose whatever money it has invested into the project and has no further liability to the lender.

Robust, well-structured and predictable cash flows are critical to supporting project finance debt. This is an area where a CfD can add significant value to a project by derisking a large proportion of its future income stream. A CfD provides a stable, inflation linked revenue stream over the long term and is backed by a creditworthy entity in the Low Carbon Contracts Company which manages the CfD scheme on behalf of the UK government and is often considered to have similar credit quality. Lenders may also require projects to be de-risked via other methods typical of a project finance structure. These could include:

- wrapped construction contracts on a fixed price basis;

- operating contracts with availability guarantees;

- long term warranty and maintenance contracts; and

- extensive insurances packages.

Loans are also typically offered on a variable interest rate basis, with a requirement to utilise an interest rate swap to fix the interest rate for the debt to reduce risk within the project.

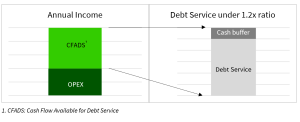

The amount of debt a project can support is calculated by forecasting the future cash flows of the project in an investment grade financial model. The model will be used to calculate the available cash flow that is forecast to be available to pay interest and capital repayments on the debt. Put simply, it is revenues less operating cost and tax. The available cash is used to backsolve the amount of debt the project can support. Debt sizing is often based on conservative forecast scenarios e.g. low energy yield forecasts and prudent macroeconomic inputs, with repayment profiles aligned to expected cash flows via debt service cover ratios (DSCR). Higher DSCRs, which are more prudent and support less debt, are attributed to more volatile, or harder to predict, “variable” revenues. For example, higher DSCRs would be applied to revenues which are subject to wholesale market price fluctuations. Lower DSCRs are applied to more predictable revenue streams, such as CfD income.

Ultimately, successfully raising project finance for wind farms hinges on clear revenue streams, disciplined financial structuring, and diligent risk management. Project developers should seek specialist advice before making any investment decisions which involve project finance.

Our experienced team would be delighted to discuss CfD, project finance or related opportunities with you:

More News…